CT of kidney stone disease

Author:

Mikael Häggström [notes 1]

This article deals with acute kidney stone disease. For non-emergent exams, see CT in recurrent kidney stone disease.

Contents

Planning

Need for imaging

Imaging is indicated in cases of flank pain and hematuria.[1]

Choice of modality

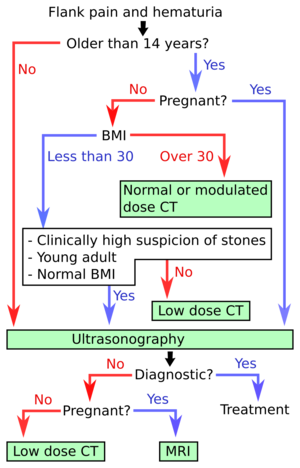

- Ultrasonography of kidney stone disease is the first-line imaging modality for patients <14 years of age and those who are pregnant. It is also the first-line investigation for thin (BMI <30) patients and there is a strong suspicion of kidney stone disease.[1] In the algorithm at right, hydronephrosis may count as a diagnostic finding of urolithiasis.

- CT of kidney stone disease is recommended for older patients, as well as those who have higher BMI and/or less specific findings.[1]

Configuration

CT without IV contrast, with low to normal radiation dose as per algorithm at right.

Evaluation

Objectives of the evaluation are mainly:[3]

- Presence of stones within the urinary tract

- Also compare to previous CTs if there is any passage of previous stones.

- Complications such as hydronephrosis (See grading below)

Further evaluation in presence of stones

- Measure the size of stones. Proper sizing of a stone is important at around 5 mm and above, since smaller stones generally pass spontaneously.[notes 2] Sizing of larger stones is also important in order to decide which treatment to choose.[notes 3]

- Assess the stone burden in the kidneys

Measurement of a 5.6 mm large kidney stone in soft tissue window (at left, with width of 400 HU, and center at 50 HU) versus skeletal window (right, W1800,C400). 145 HU is regarded as an appropriate cutoff to distinguish a stone from surrounding tissue.[4]

Hydronephrosis grading

The Society of Fetal Ultrasound has developed a grading system for hydronephrosis, initially intended for use in neonatal and infant hydronephrosis, but it is now used for grading hydronephrosis in adults as well:[5]

- Grade 0 – No renal pelvis dilation. Cutoff values for different patient populations are:

- Fetuses: An anteroposterior diameter of less than 4 mm in fetuses up to 32 weeks of gestational age and 7 mm afterwards.[6]

- Adults, defineddifferently by different sources, with anteroposterior diameters ranging between 10 and 20 mm.[7] About 13% of normal healthy adults have a transverse pelvic diameter of over 10 mm.[8]

- Pregnant women in the last two trimesters: The maximum normal expected renal pelvic diameter (97.5 percent prediction interval) is 27 mm on the right and 18 mm on the left.[9]

- Grade 1 (mild) – Mild renal pelvis dilation (anteroposterior diameter less than 10 mm in fetuses[6]) without dilation of the calyces nor parenchymal atrophy

- Grade 2 (mild) – Moderate renal pelvis dilation (between 10 and 15 mm in fetuses[6]), including a few calyces

- Grade 3 (moderate) – Renal pelvis dilation with all calyces uniformly dilated. Normal renal parenchyma

- Grade 4 (severe) – As grade 3 but with thinning of the renal parenchyma

In Swedish practice,[notes 4] the most important is a subjective classification into mild, moderate or severe, with optional mention of numerical grade (unless specifically requested in the referral).

Notes

- ↑ For a full list of contributors, see article history. Creators of images are attributed at the image description pages, seen by clicking on the images. See Radlines:Authorship for details.

- ↑ Ureteric stones less than 5 mm in diameter pass spontaneously in up to 98% of cases, while those measuring 5 to 10 in diameter pass spontaneously in less than 53% of cases.

- Gettman, MT; Segura, JW (2005). "Management of ureteric stones: Issues and controversies ". British Journal of Urology International 95 (Supplement 2): 85–93. doi:. PMID 15720341. - ↑ Small proximal ureteral calculi of less than 10 mm are best treated with shock wave lithotripsy and ureteroscopy, while those larger than 10 mm are best treated with flexible ureteroscopy combined with holmium laser lithotripsy.

- Glenn M Preminger, Section Editors:Stanley Goldfarb, Michael P O'Leary. Deputy Editor:Albert Q Lam (2018-01-19). Management of ureteral calculi. UpToDate. - ↑ NU Hospital Group, Sweden

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Brisbane, Wayne; Bailey, Michael R.; Sorensen, Mathew D. (2016). "An overview of kidney stone imaging techniques ". Nature Reviews Urology 13 (11): 654–662. doi:. ISSN 1759-4812.

- ↑ Brisbane, Wayne; Bailey, Michael R.; Sorensen, Mathew D. (2016). "An overview of kidney stone imaging techniques ". Nature Reviews Urology 13 (11): 654–662. doi:. ISSN 1759-4812.

- ↑ J Kevin Smith, Mark E Lockhart, Nicole W Berland and Philip J Kenney (2015-10-27). Urinary Calculi Imaging. Medscape.

- ↑ Lidén, Mats; Thunberg, Per; Broxvall, Mathias; Geijer, Håkan (2015). "Two- and three-dimensional CT measurements of urinary calculi length and width: a comparative study ". Acta Radiologica 56 (4): 487–492. doi:. ISSN 0284-1851.

- ↑ Laurence S Baskin. Overview of fetal hydronephrosis. Version Version 29.0. UpToDate. Retrieved on 2017-04-25. Last updated Apr 20, 2017

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Page 189 in: V. D'Addario (2014). Donald School Basic Textbook of Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology . JP Medical Ltd. ISBN 9789351523376.

- ↑ Page 78 in: Justin Bowra, Russell E (2011). Emergency Ultrasound Made Easy, Edition 2 . Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 9780702048722.

- ↑ "Sonographic evaluation of renal appearance in 665 adult volunteers. Correlation with age and obesity ". Acta Radiol 34 (5): 482–5. 1993. doi:. PMID 8369185.

- ↑ Erickson, L. M.; Nicholson, S. F.; Lewall, D. B.; Frischke, Lauraline (1979). "Ultrasound evaluation of hydronephrosis of pregnancy ". Journal of Clinical Ultrasound 7 (2): 128–132. doi:. ISSN 00912751.