Ultrasonography of intratesticular tumors

Authors:

Mikael Häggström; Authors of Creative Commons article[1] [notes 1]

Contents

Intratesticular tumors

One of the primary indications for scrotal sonography is to evaluate for the presence of intratesticular tumor in the setting of scrotal enlargement or a palpable abnormality at physical examination. It is well known that the presence of a solitary intratesticular solid mass is highly suspicious for malignancy. Conversely, the vast majority of extratesticular lesions are benign.[1]

Germ cell tumors

Primary intratesticular malignancy can be divided into germ cell tumors and non–germ cell tumors. Germ cell tumors are further categorized as either seminomas or nonseminomatous tumors. Other malignant testicular tumors include those of gonadal stromal origin, lymphoma, leukemia, and metastases.[1]

Seminoma

Approximately 95% of malignant testicular tumors are germ cell tumors, of which seminoma is the most common. It accounts for 35%–50% of all germ cell tumors. Seminomas occur in a slightly older age group when compared with other nonseminomatous tumor, with a peak incidence in the forth and fifth decades. They are less aggressive than other testicular tumors and usually confined within the tunica albuginea at presentation. Seminomas are associated with the best prognosis of the germ cell tumors because of their high sensitivity to radiation and chemotherapy.[1]

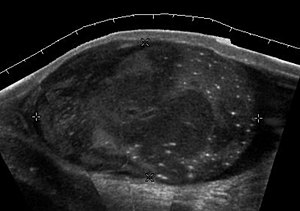

Seminoma is the most common tumor type in cryptorchid testes. The risk of developing a seminoma is increased in patients with cryptorchidism, even after orchiopexy. There is an increased incidence of malignancy developing in the contralateral testis too, hence sonography is sometimes used to screen for an occult tumor in the remaining testis. On US images, seminomas are generally uniformly hypoechoic, larger tumors may be more heterogeneous [Fig. 3]. Seminomas are usually confined by the tunica albuginea and rarely extend to peritesticular structures. Lymphatic spread to retroperitoneal lymph nodes and hematogenous metastases to lung, brain, or both are evident in about 25% of patients at the time of presentation.[1]

Nonseminomatous germ cell tumors

Nonseminomatous germ cell tumors most often affect men in their third decades of life. Histologically, the presence of any nonseminomatous cell types in a testicular germ cell tumor classifies it as a nonseminomatous tumor, even if most of the tumor cells belong to seminona. These subtypes include yolk sac tumor, embryonal cell carcinoma, teratocarcinoma, teratoma, and choriocarcinoma. Clinically nonsemionatous tumors usually present as mixed germ cell tumors with variety cell types and in different proportions.

Embryonal cell carcinoma

Embryonal cell carcinomas, a more aggressive tumor than seminoma usually occurs in men in their 30s. Although it is the second most common testicular tumor after seminoma, pure embryonal cell carcinoma is rare and constitutes only about 3 percent of the nonseminomatous germ cell tumors. Most of the cases occur in combination with other cell types. At ultrasound, embryonal cell carcinomas are predominantly hypoechoic lesions with ill defined margins and an inhomogeneous echotexture. Echogenic foci due to hemorrhage, calcification, or fibrosis are commonly seen. Twenty percent of embryonal cell carcinomas have cystic components. The tumor may invade into the tunica albuginea resulting in contour distortion of the testis [Fig. 4].[1]

Yolk sac tumor

Yolk sac tumors also known as endodermal sinus tumors account for 80%

of childhood testicular tumors, with most cases occurring before the age of 2 years. Alpha-fetoprotein is normally

elevated in greater than 90% of patients with yolk sac tumor (Woodward et al, 2002, as cited

in Ulbright et al, 1999). In its pure form, yolk sac tumor is rare in adults; however yolk sac

elements are frequently seen in tumors with mixed histologic features in adults and thus

indicate poor prognosis. The US appearance of yolk sac tumor is usually nonspecific and

consists of inhomogeneous mass that may contain echogenic foci secondary to hemorrhage.

Choriocarcinoma --- Choriocarcinoma is a highly malignant testicular tumor that usually

develops in the 2nd and 3rd decades of life. Pure choriocarcinomas are rare and represent

only less than 1 percent of all testicular tumors. Choriocarcinomas

are composed of both cytotrophoblasts and syncytiotrophoblasts, with the latter responsible

for the clinical elevation of human chorionic gonadotrophic hormone level. As microscopic

vascular invasion is common in choriocarcinoma, hematogeneous metastasis, especially to

the lungs is common. Many

choriocarcinomas show extensive hemorrhagic necrosis in the central portion of the tumor;

this appears as mixed cystic and solid components at ultrasound.[1]

Teratoma Although teratoma is the second most common testicular tumor in children, it affects all age groups. Mature teratoma in children is often benign, but teratoma in adults, regardless of age, should be considered as malignant. Teratomas are composed of all three germ cell layers, i.e. endoderm, mesoderm and ectoderm. At ultrasound, teratomas generally form well-circumscribed complex masses. Echogenic foci representing calcification, cartilage, immature bone and fibrosis are commonly seen [Fig. 5]. Cysts are also a common feature and depending on the contents of the cysts i.e. serous, mucoid or keratinous fluid, it may present as anechoic or complex structure [Fig. 6].[1]

Fig. 5. Teratoma. A plaque like calcification with acoustic shadow is seen in the testis.[1]

Fig. 6. Mature cystic teratoma. (a) Composite Image. Mature cystic teratoma in a 29 year-old man. Longitudinal sonography image of the right testis shows a multilocular cystic mass. (b) Mature cystic teratoma in a 6 year-old boy. Longitudinal sonography of the right testis shows a cystic mass contains calcification with no obvious acoustic shadow.[1]

Non-germ cell tumours

Sex cord-stromal tumours

Sex cord-stromal (gonadal stromal) tumors of the testis, account for 4 per cent of all testicular tumors. The most common are Leydig and Sertoli cell tumors. Although the majority of these tumors are benign, these tumors can produce hormonal changes, for example, Leydig cell tumor in a child may produce isosexual virilization. In adult, it may have no endocrine manifestation or gynecomastia, and decrease in libido may result from production of estrogens. These tumors are typically small and are usually discovered incidentally. They do not have any specific ultrasound appearance but appear as well-defined hypoechoic lesions. These tumors are usually removed because they cannot be distinguished from malignant germ cell tumors.[1]

Leydig cell tumors are the most common type of sex cord–stromal tumor of the testis, accounting for 1%–3% of all testicular tumors. They can be seen in any age group, they are generally small solid masses, but they may show cystic areas, hemorrhage, or necrosis. Their sonographic appearance is variable and is indistinguishable from that of germ cell tumors.[1]

Sertoli cell tumors are less common, constituting less than 1% of testicular tumors. They are less likely than Leydig cell tumors to be hormonally active, but gynecomastia can occur. Sertoli cell tumors are typically well circumscribed, unilateral, round to lobulated masses.[1]

Lymphoma

Clinically lymphoma can manifest in one of three ways: as the primary site of involvement, or as a secondary tumor such as the initial manifestation of clinically occult disease or recurrent disease. Although lymphomas constitute 5% of testicular tumors and are almost exclusively diffuse non-Hodgkin B-cell tumors, only less than 1 % of non-Hodgkin lymphomas involve the testis.[1]

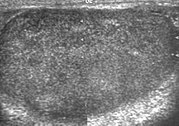

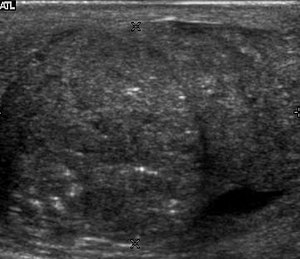

Patients with testicular lymphoma are usually old aged around 60 years of age, present with painless testicular enlargement and less commonly with other systemic symptoms such as weight loss, anorexia, fever and weakness. Bilateral testicle involvements are common and occur in 8.5% to 18% of cases. At sonography, most lymphomas are homogeneous and diffusely replace the testis [Fig. 7]. However focal hypoechoic lesions can occur, hemorrhage and necrosis are rare. At times, the sonographic appearance of lymphoma is indistinguishable from that of the germ cell tumors [Fig. 8], then the patient’s age at presentation, symptoms, and medical history, as well as multiplicity and bilaterality of the lesions, are all important factors in making the appropriate diagnosis.[1]

Leukemia

Primary leukemia of the testis is rare. However due to the presence of blood-testis barrier, chemotherapeutic agents are unable to reach the testis, hence in boys with acute lymphoblastic leukemia, testicular involvement is reported in 5% to 10% of patients, with the majority found during clinical remission. The sonographic appearance of leukemia of the testis can be quite varied, as the tumors may be unilateral or bilateral, diffuse or focal, hypoechoic or hyperechoic. These findings are usually indistinguishable from that of the lymphoma [Fig. 9].[1]

Fig. 9. Leukemia. Diffuse hypoechoic infiltrative lesions are seen involving the whole testis, indistinguishable from that of the lymphoma.[1]

Epidermoid cyst

Epidermoid cysts, also known as keratocysts, are benign epithelial tumors which usually occur in the second to fourth decades and accounts for only 1–2% of all intratesticular tumors. As these tumors have a benign biological behavior and with no malignant potential, preoperative recognition of this tumor is important as this will lead to testicle preserving surgery (enucleation) rather than unnecessary orchiectomy. Clinically, epidermoid cyst cannot be differentiated from other testicular tumors, typically presenting as a non-tender, palpable, solitary intratesticular mass. Tumor markers such as serum beta-human chorionic gonadotropin and alpha-feto protein are negative. The ultrasound patterns of epidermoid cysts are variable and include:

- A mass with a target appearance, i.e. a central hypoechoic area surrounded by an

echolucent rim;

- An echogenic mass with dense acoustic shadowing due to calcification;

- A well-circumscribed mass with a hyperechoic rim;

- Mixed pattern having heterogeneous echotexture and poor-defined contour and

- An onion peel appearance consisting of alternating rings of hyperechogenicities and

hypoechogenicities.[1]

However, these patterns, except the latter one, may be considered as non-specific as heterogeneous echotexture and shadowing calcification can also be detected in malignant testicular tumors. The onion peel pattern of epidermoid cyst [Fig. 10] correlates well with the pathologic finding of multiple layers of keratin debris produced by the lining of the epidermoid cyst. This sonographic appearance should be considered characteristic of an epidermoid cyst and corresponds to the natural evolution of the cyst. Absence of vascular flow is another important feature that is helpful in differentiation of epidermoid cyst from other solid intratesticular lesions.[1]

Notes

- ↑ For a full list of contributors, see article history. Creators of images are attributed at the image description pages, seen by clicking on the images. See Radlines:Authorship for details.

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 Content originally copied from: Mak, Chee-Wai; Tzeng, Wen-Sheng (2012). Sonography of the Scrotum . doi:. from Kerry Thoirs. Sonography. ISBN 978-953-307-947-9Script error: No such module "check isxn"., Published: February 3, 2012, under the CC-BY-3.0 license.